資料提供:臺南市政府教育局承辦人王雪瀞

為凝聚健康促進學校共識,提升健康專業知能,激發教學創意,臺南市政府教育局於111年12月23日假臺南市永康區大灣國小菁英館辦理「臺南市111年度健康促進學校成果觀摩暨增能研習」,期望透過各議題中心學校、績優學校成果展示與分享收觀摩及經驗交流之效,落實健康促進理念,促進身心靈健康,營造優質健康校園文化。

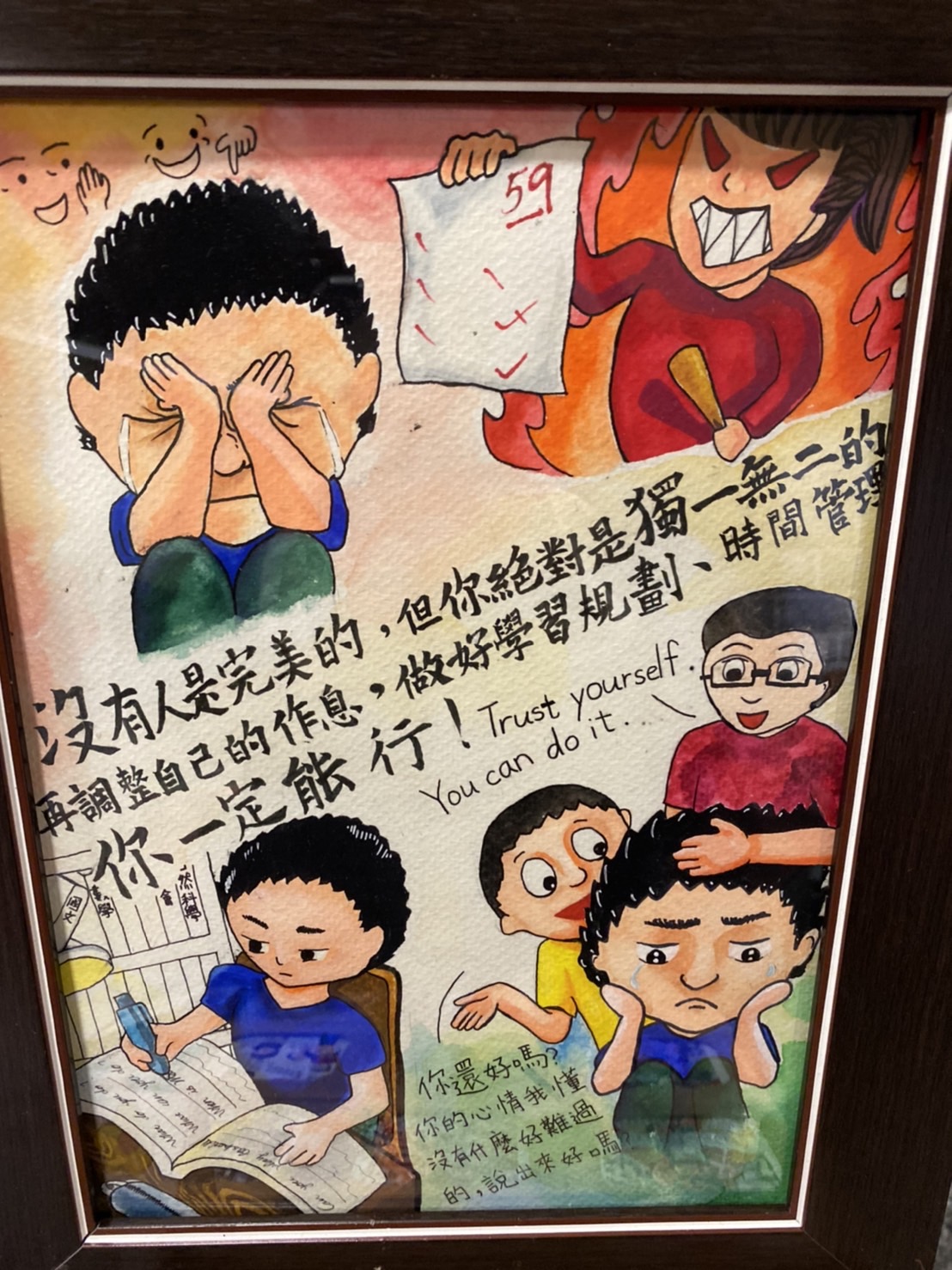

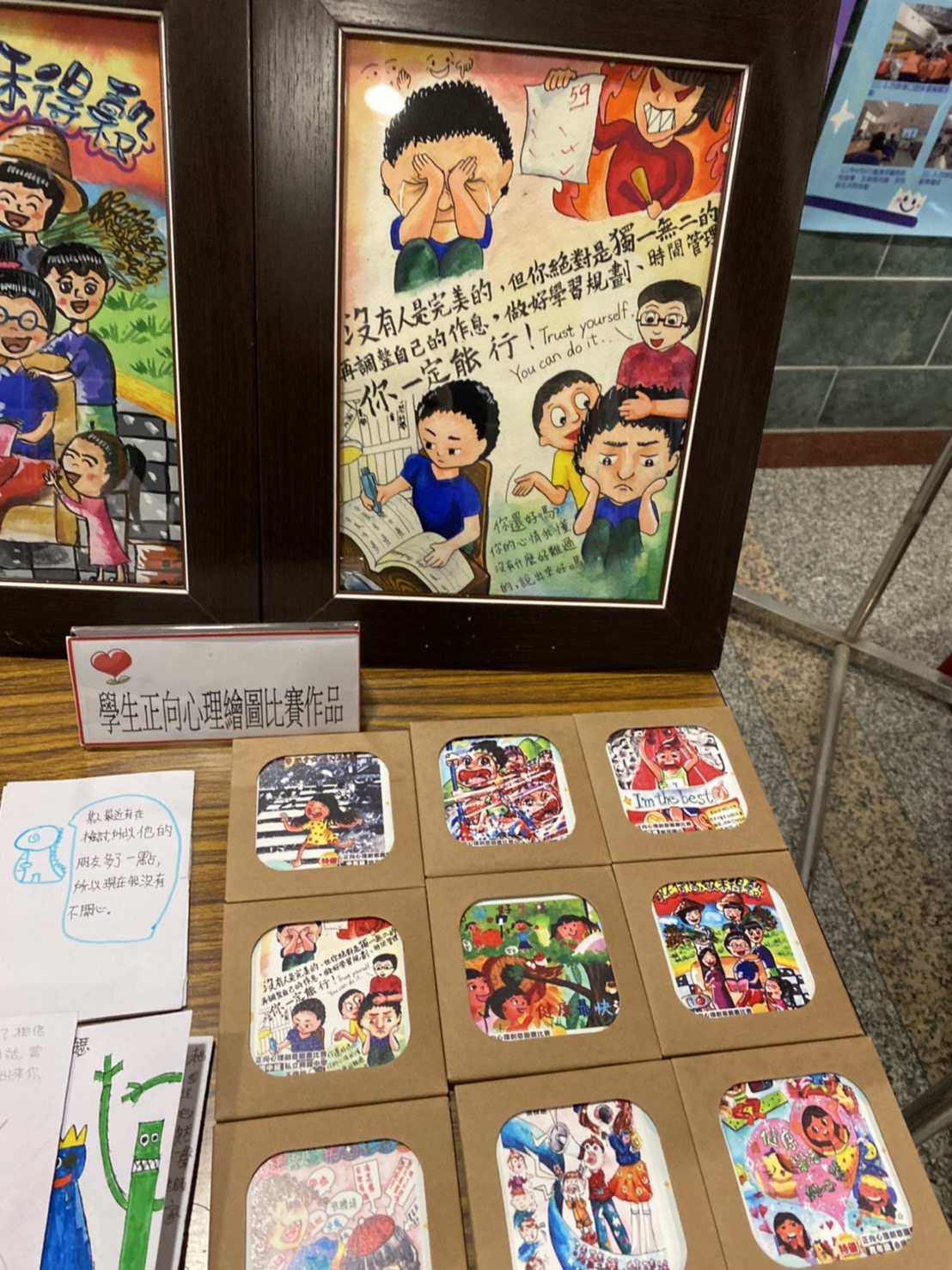

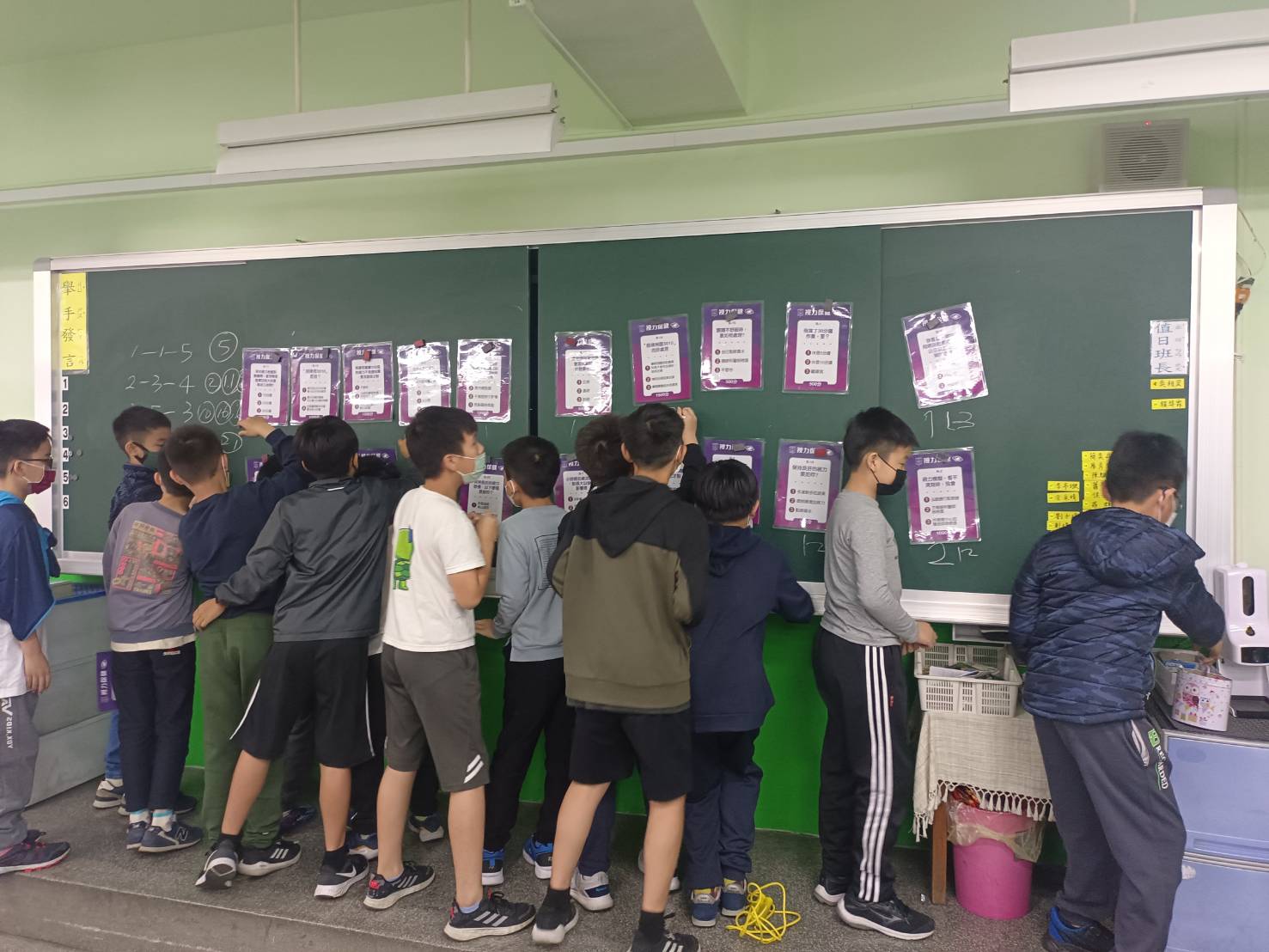

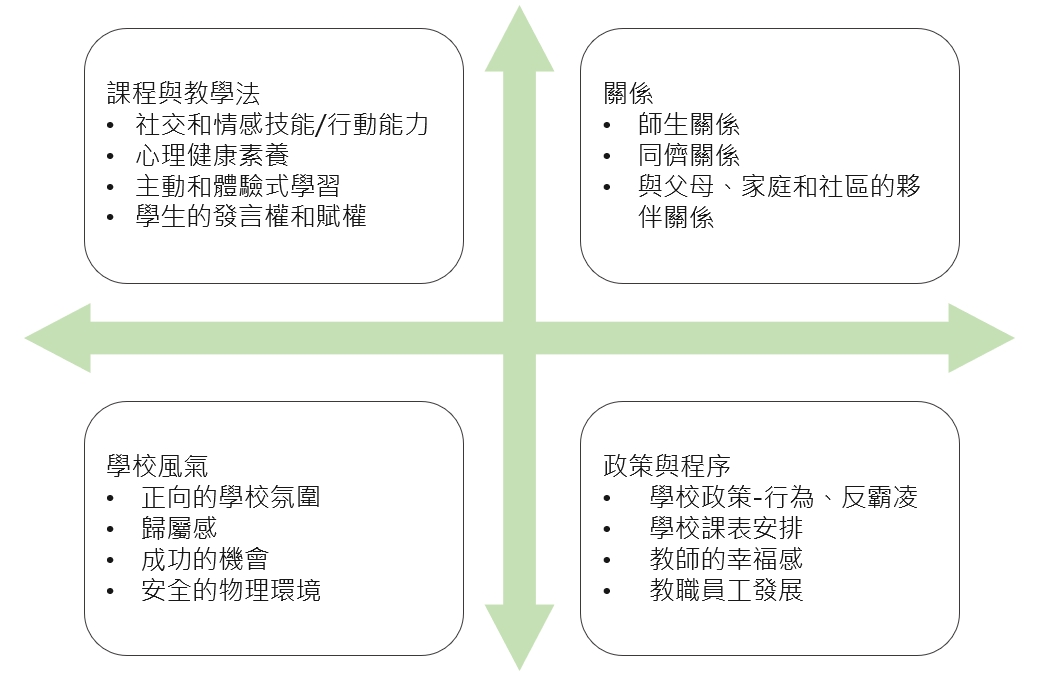

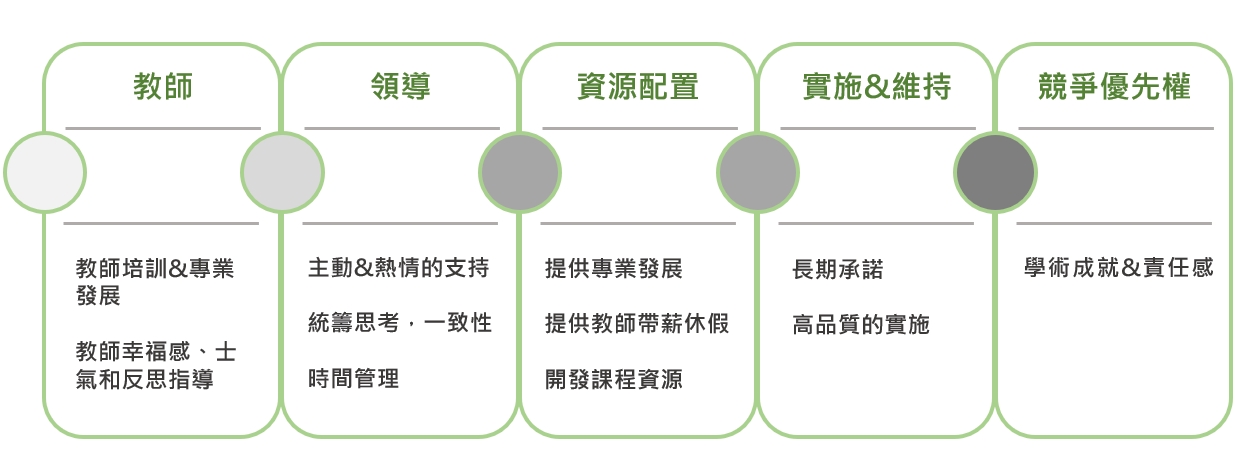

當日活動共有300人出席,內容包含110學年度健康促進議題中心學校執行成果之靜態展覽,健康促進答喙鼓、校園健康主播影片欣賞、增能講座、議題中心學校及績優學校推動經驗分享,另與中華醫事科技大學視光系合作於展示區提供視力保健宣導與驗光體驗活動等。開幕式由臺南市政府教育局楊智雄主任秘書致詞及頒獎,接著由健康促進學校輔導計畫主持人張鳳琴教授說明111學年度健康促進學校輔導計畫推動方向與重點。110-111學年度的健康促進學校主軸為「健康幸福校園」,期望透過推動「正向心理健康促進」議題,提升學校師生的「五正(正向情緒、正向參與、正向關係、正向意義、正向成就)四樂(樂動、樂活、樂食、樂眠)」,因此市府也特別邀請國立臺灣師範大學連盈如教授分享正向心理健康促進校本推動策略,使與會人員更加了解實務現場如何推動。

增能講座結束後,由臺南市政府教育局陳宗暘科長進行業務簡報,並請臺南市永康復興國小及新進國小進行績優學校經驗分享,永康復興國小提供榮獲前後測成效評價成果報告特優學校推動策略,由學校政策面評估需求、規劃執行、建立共識,分年段落實健康教學活動,引發家長關心與參與等;新進國小則由六大面向分享健康體位特優學校推動經驗,融入正向心理健康促進,營造健康幸福的校園。

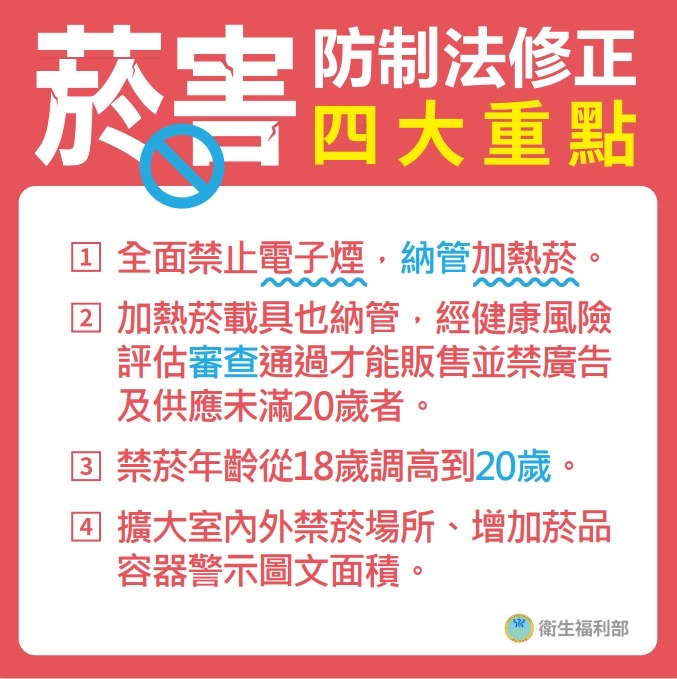

此外,各議題中心學校與協力學校推動成果豐富,視力保健議題中心日新國小分享推動健康護照,結合榮譽制度獎勵學生,透過學習單強化學童自主管理能力,並與課後安親機構合作,提升對學童視力保健的重視等策略。口腔保健議題中心裕文國小分享議題執行成效及實證新知,推動督導式潔牙,潔牙小隊學習潔牙技巧入班宣導,結合牙醫師提供專業服務等。健康體位議題中心新進國小分享甜蜜蜜城市如何在疫情攪局及生生用平板等不利因素下,透過飲食課程、多元體能活動及情境營造,增加正向心理活動,力推健康體位議題。菸檳防制議題中心西港國中以多元策略的校園菸檳危害防制教育成效,探討分享議題成果。性教育(含愛滋病防治)議題中心忠孝國中以健康促進學校及聯合國永續發展目標談起,透過前後測數據分析擬定改善計畫策略。全民健保(含正確用藥)議題中心復興國中分享校群運作及珍惜健保資源聰明就醫具體作為等。最後由健康促進輔導委員及臺南市政府教育局張惟琇股長帶領進行綜合座談,為活動畫下精彩句點。

感謝臺南市教育現場的師長們與家長共同努力,打造幸福正向的學習環境,守護學子身心健康,使正確的健康知識態度與技能普及於校園,並延伸到社區與家庭,共創健康幸福的臺南府城。